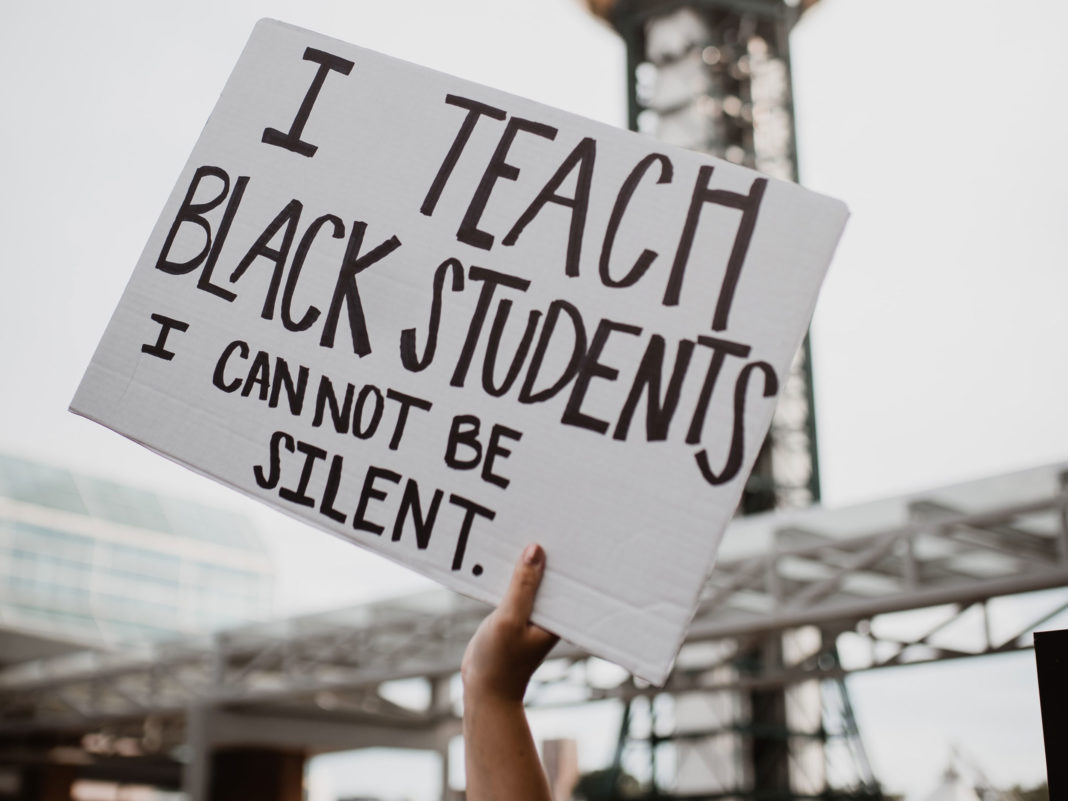

When you hear the word school, what thoughts and feelings do you have? What memories and associations does your mind conjure up? If you were or currently are a student of color, no doubt, trauma permeates your soul. American schools were never intended or designed for students of color. The same is true in the present-tense: American schools are not intended or designed for students of color.

Before I ever stepped my pre-kindergarten foot inside an elementary school, I was already sent the message that I did not belong. I was four years old when the school readiness proctor told my mom that I should not begin school because I did not know enough English. It is a common microagression to assume students of certain ethnicities do not speak English. Not only did I begin kindergarten against the test administrators recommendations, but I also graduated a semester early, summa cum laude.

Similar experiences to this testing bias continued throughout my K-12 years: the other students of color and I were put into a box where the climate swirled with white-centric perspectives and curriculum, microaggresions, lack of consideration for cultural norms, and blatant racism. In elementary school, I always felt different and separate, but I was not exactly sure why. Was it that I did not have teachers who looked like me? Was it that books by authors of color about people of color were absent from our school library? Was it that we only learned about non-white cultures as an isolated, exoticized shit attempt at “multiculturalism”? Was it kids pulling on their eyes and spewing racist words? Was it me getting asked to be the token Asian and dress up in my traditional clothing (aka my costume) for a school program? These experiences are just a fraction of the experiences that contributed to my negative feelings about school as a young child.

Middle school was the stage in life where I began to openly question authority (primarily my teachers), challenge the status quo, and repel orthodoxy. Yes, I know many pre-teens become rebellious at this age, but after careful reflection, it was more than the quintessential teenage angst: I was actually defying racism and white supremacy. Teachers and students used racial slurs with no consequence, and the curriculum was just as bad as these derogatory comments.

In high school, I was a walking paradox, trying to fit in, simultaneously doing everything in my power to fit out. Learning in middle school that challenging my teachers was not a successful method, I changed my tactics in high school to walking out of class or not attending at all. I vividly remember a teacher saying that there were no intelligent black people in existence and me looking around at my classmates like, “Yo, why doesn’t anyone have a problem with what she just said?” This was one of the many times that I chose to leave class.

School beat me up and left me for dead: it is no wonder why we have an achievement gap and why students of color are less likely than their white peers to graduate high school or go on to pursue higher education. Even so, I gave education one more chance and went to college: I was in a cohort made up of students of color, I leaned on multiple resource centers for marginalized students, and I had mentors and educators of color. Having teachers who resemble you makes a significant positive impact on the lives of students. This is why it is monumental to have organizations like The Coalition to Increase Teachers of Color and American Indian Teachers in Minnesota and efforts to recruit and retain teachers that are more representative of our student populations.

Fast forward two decades, and here I am, working for the very institution that crushed me over and over again. Why would I return? I knew I could and must make a difference for marginalized students. From a combination of my own childhood experiences and the teacher-training I had, I felt that I would have the greatest impact in urban schools, so that is where I applied. The inequities for students of color also exist for teachers of color. Here I was with a perfect GPA, a few credits short of my master’s degree, excellent recommendations, and most importantly a face that looked like the student populations where I applied. It didn’t matter! They did not want me; I did not belong . . . again.

I started looking for teaching positions in urban areas out of state. Clark County School District in Las Vegas, Nevada was recruiting teachers. One of the important issues to me was the underrepresentation of minorities in gifted programming. I had highly gifted students of color in my classes, but they were never referred for gifted programming. It was obvious to me how bright these learners were. One of these students was well-known for his “defiant” behavior. Teachers talked about how he argued with adults and was aggressive both verbally and physically. This student was brilliant, funny, candid, passionate, persistent, and inquisitive. Sadly, it is common practice to focus on the behavior of black and brown students, rather than their talents and potential, and it is no secret that students of color are disproportionately subject to disciplinary actions.

What happens in Vegas does not stay in Vegas. I eventually made my way back to The Land of 10,000 Lakes and brought my experiences with me to classrooms in Minnesota suburbs. After sixteen years of teaching, I still see similar issues I grew up with as a student, but now I see these racial inequities through the lens of a teacher and mother. As early as pre-kindergarten, my children have experienced racial injustices in the very place that is supposed to lift them up and give them wings. My child´s gauge of a good day at school depended on how he behaved in class (from the teachers’ white-normed perspective), rather than his successes and achievements. My child was isolated and segregated from classmates based on classroom seating and expectations. My child expressed disdain for his skin color because comments and incidents at school went uncorrected. My children were not differentiated for and their needs went unserviced; we had to move school districts to get access to gifted programming that my children qualified for. We must not be still in a system–a world–where some children are treated as less-than. Here are some viable solutions that we must demand to dismantle racism in educational institutions:

- Diversify the white-centric curriculum and perspectives: districts need to develop and use culturally relevant, anti-racist pedagogy and curriculum. For example, there should be ample literature written by authors of color, including characters of color in complex roles (not just stock characters in oppression stories). This is more than just creating a diverse collection of books–teachers need to teach students how to uncover biases and examine texts to see who they serve, and there needs to be discussions about what role race plays in readings.

- Provide different types of assessments and ways students can show what they know. Study the cultural norms for different ethnicities and ensure there is a place for these norms in the classroom. For instance, there is a strong emphasis on writing as a communication tool in schools; however, speaking is a preferred mode of communication for some cultures and should have equal value. I am not saying that we do not teach writing; rather, we need to teach skills that provide students of color access to the dominant culture, simultaneously disrupting this very culture in power.

- Create safe spaces in schools for students of color to gather, share experiences, and lean on each other for support. Mentors and teachers of color should be involved in facilitating these groups.

- Recruit and incentivize teachers of color, as early as high school, to make education an attractive option. Additionally, schools need to take measures to retain and support their teachers of color.

- Mandate comprehensive and ongoing training and staff development on cultural competency.

- Eliminate referral bias for gifted programming by providing universal, culturally relevant screening and testing.

- Evaluate and change which behaviors are rewarded and which behaviors are punished. For instance, overlapping talk and interrupting are discourse patterns for some cultures; nevertheless, these behaviors are often admonished in the classroom.

- End discipline measures that push students out of the classroom and out of the processes; implement restorative practices that keep students part of the conversation.

We must improve systemic racism in schools. Do not be still: school must be intended and designed for students of color.

Love this piece by Ali Alowonle!

Our daughter, and our family, learned so much through Ali’s elementary school classroom that persists a decade later in our communications at home. Thank you!

Comments are closed.